Split Vessels: Jenny Hata Blumenfield

Jenny Hata Blumenfield, Pictograms, 2019. Ceramic with glaze.

Hi! My name is Alyson, and I’m this year’s Getty Marrow Intern at AMOCA. I recently graduated from Chapman University with a BA in Art History and a minor in Anthropology.

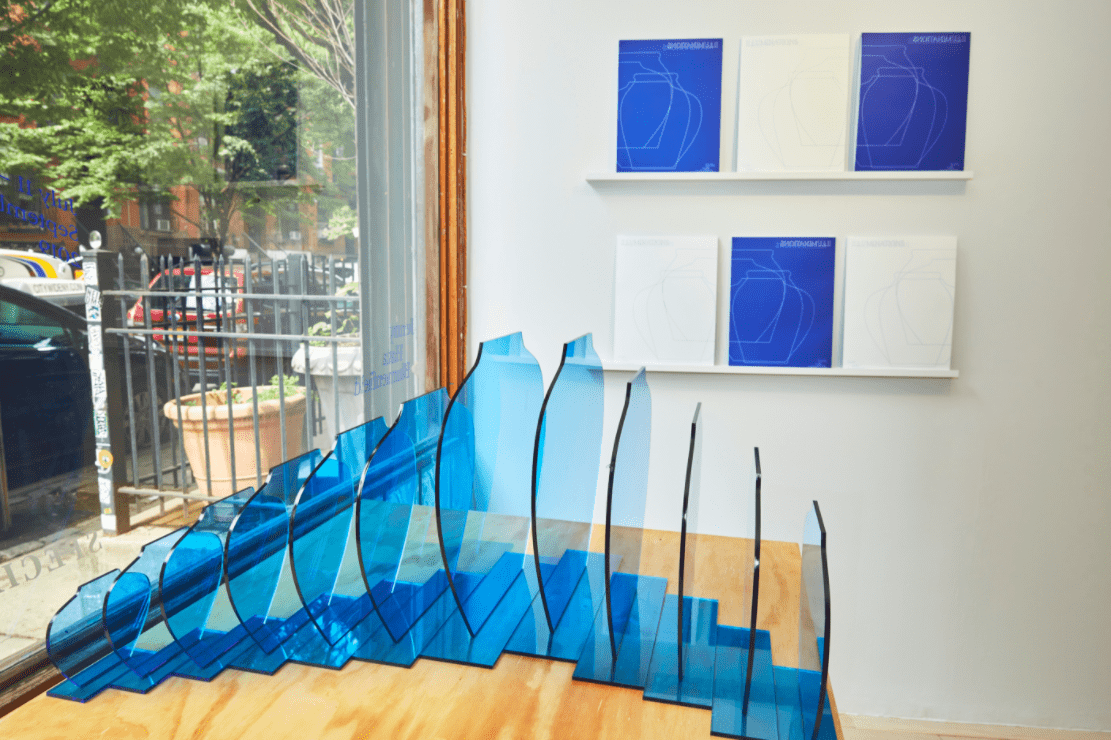

I first saw Jenny Hata Blumenfield’s work at Craft Contemporary’s 2020 Clay Biennial: The Body, The Object, The Other. I was intrigued by her use of photography, and these colorful plastic boards shaped as vessels, which were used alongside dissected ceramic works. My eyes scanned the small installation grouping, discovering vessels in various forms and stages. It was strange because while her work involves the traditional vessel form, almost none of it is functional. One of Blumenfield’s goals with her work is for viewers to have questions, and to become curious about the various forms and presentations of the vessel.

Blumenfield was born in Los Angeles in 1988, and currently works out of a studio in the city.

Her decision to work in clay stems from an understanding that ceramics can be an in-between artistic material, moving between the fine art and craft realms. Blumenfield relates to the “othering” that clay experiences in the artistic world, explaining in an interview with Christie’s:

“Being half-Japanese and half-American, I always felt stuck between two cultural identities. I’m these two halves that really can’t seem to connect — I just exist in the in-between.”

In order to explore this feeling, Blumenfield halves a lot of her vessels to visualize how she feels as only being half of a cultural identity. There is a strong emphasis on material and breaking boundaries between various forms. Recent work involves two-dimensional drawings of vessels, which Blumenfield then recreates out of planes of colored lucite. Once positioned to allow sunlight to interact with the work, two-dimensional shadows of the works are cast back down onto the ground, creating a circular progression from flat to physical, and flat yet again.

The symbolic history of the vessel is charged in a different way; vessels and containers have largely been viewed as feminine objects. An example would be the yoni and lingam in Hindu tradition, where the yoni is a feminine, concave vessel which receives the masculine lingam. Greek and Roman culture also regarded vessels as feminine because of the possibility of fertility, associating the shape of a woman’s body with amphorae. Blumenfield is aware of this association, and explored it in a 2019 installation, The Vessel as Female, where a model is photographed with a yellow vessel painted on her back, and posing among two and three dimensional vessels.

Belonging to more than one cultural group is something which I’ve thought about a lot throughout my life. While I do have Mexican heritage, it feels hard to be accepted into it when it is not my entire identity. It’s something I think about a lot now, and remain aware and curious about. It’s why I was drawn to Mesoamerican, Latin American and Chicano Art while doing my undergrad in Art History, and why I wrote my senior thesis on an avant-garde Chicano Art collective. Blumenfield’s work resonates with me because of this duality of identity, and it’ll be interesting to watch to see how she considers this in future work.

Alyson Brandes is a graduate of Chapman University and a 2020 Getty Marrow Undergraduate Intern at AMOCA. During her internship, Brandes writes periodically for AMOCA.org, and posts on Instagram and Facebook on Tuesdays. Read her blog posts:

- Asco and the Hierarchies of Art

- Feminizing Brutalism: Ruby Neri and Her Giant Vessels

- The Cinematic Roots of Clay

- The Colorful World of Miss Anna Valdez

- Split Vessels: Jenny Hata Blumenfield

- The Legend of Beatrice Wood

- Nicole Seisler: Rituals, Processes and Documentation

- Ashwini Bhat

- Nancy Selvin: The Abstraction of Art History

- New Acquisitions: Trompe l’Oeil

- Kim Tucker’s “Primal Beings, Ghosts, and Human Dummies”

- Blue Boys and Farmers: Howard Kottler’s Queer Plates

- At the Center of Nicki Green

- The Legacy of Sascha Brastoff

- End of Internship Reflection