The Legend of Beatrice Wood

Beatrice Wood, 1985. Photo by Jim Hair.

Hi! My name is Alyson, and I’m this year’s Getty Marrow Intern at AMOCA. I recently graduated from Chapman University with a BA in Art History and a minor in Anthropology.

A quick Google search for Beatrice Wood (1893-1998), ties her to the Dada art movement of the early 20th century, and even calls her the “Mama of Dada.” This was not the introduction I had to Wood while I began looking through her ceramic works this summer, a couple of which are in AMOCA’s permanent collection. I first learned about Beatrice Wood as the woman who crafted signature luster and lava glazed ceramics up until her death at 105 years old in her Ojai, California community surrounded by like-minded artists and the Indian philosopher Jiddu Krishnamurti. While Woods is now also regarded as one of the leading women in early California ceramics, her story starts much, much earlier than what is remembered from these later years.

Beatrice Wood was born into a wealthy San Francisco family in 1893, and moved with them to New York after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. She was sent to Paris to study acting and art before moving back to New York as the first World War began. Once in New York, Wood met artist Marcel Duchamp and writer Henri-Pierre Roche while visiting her friend, composer Edgar Varese, in the hospital. This meeting influenced Wood’s personal ideologies and artistic vision for the decades to follow, as the trio became known for their creation of The Blind Man, a Dadaist art journal, in 1917.

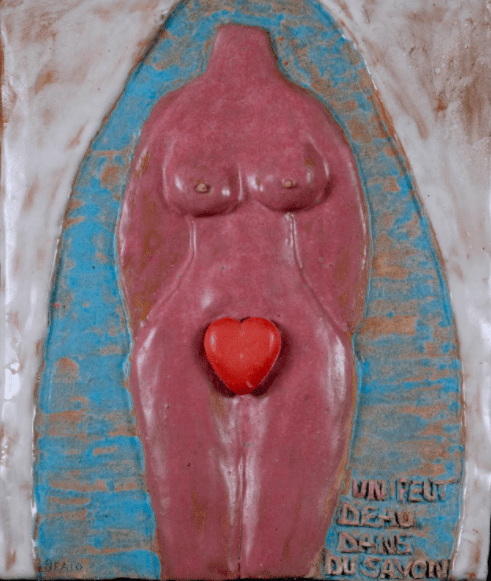

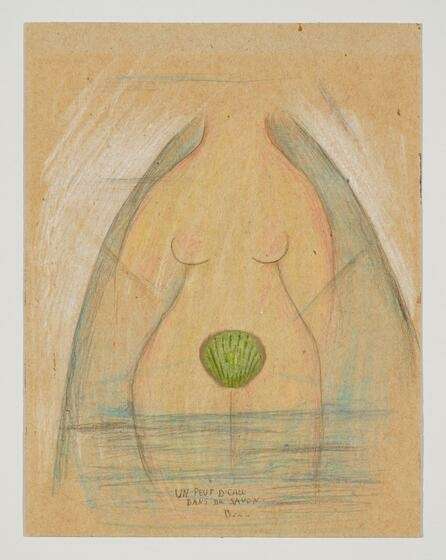

The Dada movement came as an early 20th century response to World War I, in which artists and writers came together in an effort to reject the reason and aesthetics associated with modern capitalism, and instead chose nonsense and irrationality. Some of the most widely recognized Dadaist works came from Wood’s close friend, Marcel Duchamp, including Fountain (1917), the porcelain urinal signed “R. Mutt,” and L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), a copy of da Vinci’s Mona Lisa with facial hair painted on. It is oftentimes forgotten in general art history that Wood’s submission to the Society of Independent Artists’ exhibition, which Duchamp created Fountain for, caused just as much of an uproar as Fountain did when it was showcased. The work, titled Un peut (peu) d’eau dans du savon (A little water in some soap) from 1917 showed a painting of a nude woman’s torso with a real bar of soap affixed to the pubic triangle. Wood would go on to recreate this work again on paper, and in clay, likening the woman to that of Boticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486).

Wood did not have any prior experience in ceramics when, at age 40, she signed up for a class at Hollywood High School to make a teapot to match a larger set she owned. She would never make that teapot, but what followed were years of innovation in ceramics that have put Wood on AMOCA’s list for a future exhibition of women ceramicists working in California. It’s not surprising that Wood transitioned from the Dada movement to clay – ceramics has a history of being the “outsider’s” material of choice, with room for endless possibilities in form, glazing and firing, and Wood was up for the challenge. Nothing had stopped her from being a leading voice among her peers in New York, and so once she moved to California in the middle of her life, she was drawn to the newest and next thing. Wood attributed her longevity to “art books, chocolates, and young men,” but I truly believe that it was her genuine love for life and drive to consistently be on the cultural forefront, and trying new things that created a sort of immortal sense about her.

Blue Chalice, earthenware, luster glaze, 1985.

Blue Lustre Double Necked Bottle with Braided Decoration, earthenware, luster glaze, 9 x 5.8 x 5.8 in., 1969.

Lava Glaze Bowl, earthenware, lava glaze, 5 x 11.5 x 11.5 in., 1960.

Tides in a Man’s Life, earthenware, luster glaze, 11.5 x 5.5 in., 1988.

Un peut (peu) d’eau dans du savon (A Little Water in Some Soap), glazed earthenware, heart shaped bar of soap, 11.75 x 9.75in., 1980.

Un peut (peu) d’eau dans du savon (A Little Water in Some Soap), colored pencil, graphite pencil and soap on board, 11 x 8.5 in., 1917, recreated 1976.

Alyson Brandes is a graduate of Chapman University and a 2020 Getty Marrow Undergraduate Intern at AMOCA. During her internship, Brandes writes periodically for AMOCA.org, and posts on Instagram and Facebook on Tuesdays. Read her blog posts:

- Asco and the Hierarchies of Art

- Feminizing Brutalism: Ruby Neri and Her Giant Vessels

- The Cinematic Roots of Clay

- The Colorful World of Miss Anna Valdez

- Split Vessels: Jenny Hata Blumenfield

- The Legend of Beatrice Wood

- Nicole Seisler: Rituals, Processes and Documentation

- Ashwini Bhat

- Nancy Selvin: The Abstraction of Art History

- New Acquisitions: Trompe l’Oeil

- Kim Tucker’s “Primal Beings, Ghosts, and Human Dummies”

- Blue Boys and Farmers: Howard Kottler’s Queer Plates

- At the Center of Nicki Green

- The Legacy of Sascha Brastoff

- End of Internship Reflection