February 11–April 1, 2006

Opening Reception: February 11, 6 p.m.-9 p.m.

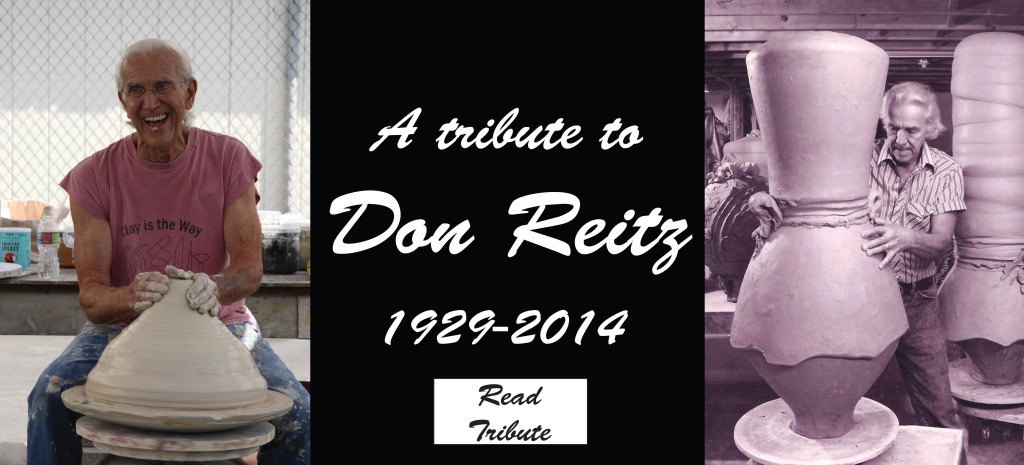

Don Reitz received his M.F.A from New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University in 1962. That same year he accepted a position at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where he taught ceramics for 26 years.

Had it not been for dyslexia, Don Reitz might have been a poet. He might have employed the written word to convey his inner thoughts and emotions, using sentences rich with adjectives and textured with superlatives. But in his youth, when Reitz’s ability to process the written word was found wanting, he discovered his true talent lay in the visual arts: wood shop, drawing, painting, and ultimately ceramics. His extraordinary artistic skills, refined over time, became a means of recording expression, and as such, developed into his own form of poetry.

Reitz refers to his medium of choice as “dirt.” Simply put, clay is dirt or earth, and “burnt earth” is pottery. Reitz recalls a childhood fascination with digging in the dirt, building dirt dams, or filling ant holes with dirt only to watch them being re-excavated by the industrious insects. Dirt also served as a handy sketch pad on which to scratch diagrams or maps. Speaking of himself, Reitz said, “I am from the dirt as my pots are from the dirt–from the skin of this planet.” Reitz, who is famous for his textured ceramic surfaces, continues his analogy: “my surfaces today are about the conditions of dirt in various forms–wet, dry, slurry, powder, all those things.”

Dynamic ceramic surfaces are also determined by the firing of a kiln. Reitz re-introduced the age-old technique of salt firing enhanced by a few new tricks. He keeps the process alive by varying the way the kiln is stacked, by maintaining a relatively uneven temperature, by adding oil or wood through the burner ports or tossing ashes, chunks of feldspar, or even fruits such as apples or oranges into the fire. The speed of the cooling process offers still another variant, allowing for color value changes or crystal formations in the glaze.

A central theme of the Don Reitz story is one of pain and transfiguration. In 1982, Reitz was involved in a near-fatal car accident. Adding to the trauma, Reitz’s father died just days after Don was hospitalized, and Sara, Reitz’s five-year-old niece was diagnosed with cancer of the kidney. These personal trials caused a brief but intense period of introspection. Unable to use a potter’s wheel during his recovery, Reitz began to paint with slips on slabs of clay rolled out by his students. This unique body of cathartic “story-telling” work is replete with child-like drawings of characters and symbols expressing his personal and societal frustration. Later Reitz returned to revive and reinvent his earlier, highly-regarded vessel forms. Visual communication is Reitz’s special gift. It can be seen in the simplicity of his early utilitarian ware–the angle of a handle or direction of a spout that makes pouring more a celebration than a routine act. And, it can be seen in the complex composition of his mature, massive forms whose megalithic size and bold construction commemorate the forces of nature. Grouped together they could be imagined as a modern-day Stonehenge arranged to celebrate the Earth.