Feb 12–April 2, 2005

Women’s “Werk”: The Dignity of Craft will contrast the artistic accomplishments of Susi Singer and Marguerite Wildenhain, two important ceramic artists who began their creative careers during the 1920s and exemplify the Modernist spirit. The artists participated in two related—yet distinctive—European design reformation movements. At age seventeen, Singer won a scholarship to train at the famous Wiener Werkstätte of Vienna, Austria, where she learned to create exquisite ceramic figures. At nearly the same time, Wildenhain became a student at the German Bauhaus where, after mastering the fundamentals of ceramics, she went on to design superbly formed, functional tableware for industrial production and become well-known for her teaching and studio pottery.

Historic craft exhibitions, collector and antique clubs, and on-line auctions have encouraged the current enthusiasm for early crafts-based Modernism. The movement that swept through England, Europe, and the United States just after the turn of the century is credited with initiating a fresh approach to design, but the movement was much more than an art style. It was fraught with socialist idealism and near-religious zeal for creating innovative design, countering the Industrial Revolution, reforming the wage system, and aspiring to make beautiful objects affordable.

Women’s “Werk:” The Dignity of Craft presents the artistic accomplishments of Susi Singer (1891-1955) and Marguerite Wildenhain (1896-1985). At first glance, these ceramists seem as different as night and day. To be sure, their work is very different, for while Wildenhain produced vessels on a potter’s wheel, Singer created brightly glazed, fanciful figures. However, this exhibition will reveal the intriguing parallels and the disparities of their lives, and it will undoubtedly demonstrate the impact both Singer and Wildenhain had on the evolution of ceramics.

Women’s “Werk”

As young women, both Singer and Wildenhain had high artistic aspirations. With an uncommon, natural talent, Singer wanted to be a painter. These aspirations were discouraged by Joseph Hofmann, one of the founders of the Wiener Werkstätte, who directed her toward the “applied arts,” specifically to the ceramics workshop. There, though her work won many awards, she was still relegated to being a maker of “figurines,” a label that lacked the prestige of the term “fine art.” At the same time, Marguerite Wildenhain was trained under Bauhaus master sculptor Gerhard Marcks and master potter Max Krehan. Wildenhain’s hope was to become a sculptor, but Marcks advised Wildenhain of the impossibility for a woman to succeed in this selective, male-dominated medium. Wildenhain resigned herself to her craft and concentrated her efforts on becoming an exceptional potter.

Because of their Jewish ancestry, both women had to flee Europe prior to World War II to escape Nazi persecution. They both settled in California, Wildenhain in the rustic Northern landscape and Singer in the glamorous Los Angeles area; these new environments further shaped their artistic careers. Both developed a special relationship to the ceramics department at Scripps College in Claremont, CA. In 1946, Singer was awarded a grant from the College’s Fine Arts Foundation to explore glazes and to produce a number of glazed sculptural pieces for the department. During her short time at Scripps, Singer taught sculpture in an on-campus extension class. Likewise, Wildenhain was invited to conduct a workshop in 1952 by the ceramics department chairman, Richard Petterson. Though not documented, it is more than likely that Singer and Wildenhain knew each other, as they both appeared in the first Scripps College Bi-Annual Ceramics exhibition, as well as in six succeeding exhibitions. In 1947, they were shown along with such famed potters as Otto and Gertrud Natzler, Laura Andreson, Henry Varnum Poor, and William Manaker. Women’s “Werk:” The Dignity of Craft traces the successes and the frustrations of Wildenhain’s and Singer’s ceramic careers both before and after their relocation to California.

Historic Background

At the end of the nineteenth century, Europe was plagued with social and political unrest. Both Susi Singer and Marguerite Wildenhain were born into this unrest, and their lives could not help but be shaped by the experience. Infused with nationalism, secret alliances between nations, and a global economy fueled by the Industrial Revolution, the continent was perfectly positioned for the disastrous conflict of World War I. During such chaotic times, people have often sought idealistic answers and placed their hopes on societal reordering, futuristic innovation, political ideology, or spiritual leaders. As art reflects life, it was into this climate that the artistic communities of Austria and Germany independently sought to create an aesthetic utopian vision, patterned after the philosophy of Englishman William Morris.

In pre-World War I Vienna, this vision was reflected by a group of artists who rejected the traditionally elaborate proclivity toward architecture and design in favor of a simpler “modern” style. They adopted a revolutionary position, believing that art school, craft workshops, and exhibitions should be integrated so as to offer to their patrons cohesively designed “whole” living environments. The resulting craft workshop, referred to as the Wiener Werkstätte (1903-1930), sought to restore solid, innovative design through the mutual cooperation of both artist and craftsman, with the aspiration to reaffirm an aesthetic value that was nearly always missing in mass manufactured items.

A similar movement was begun in Germany. Founded in 1907 by Hermann Muthesius, the Deutsche Werkbund was a pioneering association of artists and industrialists dedicated to engineering economic and cultural reform through the modernization of German architecture and design. In 1919, under the leadership of Walter Gropius, the Werkbund was succeeded in Weimar by the Bauhaus, and a new form of academic instruction for an industrial society was initiated, one that theoretically overcame the fallacies in Morris’s “craftsman’s culture.” The Bauhaus advocated classes taught in tandem by both master craftsmen and artist-professors. This new form of training sought to combine imaginative concepts with practical knowledge of the materials. The Bauhaus was responsible for a new sense of functional design and the formation of the axiom “form follows function.”

While both Austrian and German ideologies sought to elevate craft, embracing a broader definition of art that now included architecture, typography, furniture, textiles, ceramics, and even wallpaper, there were also important differences. For instance, while the Wiener Werkstätte rejected mass production and therefore catered to the elite class, the Bauhaus ideal was to design for industry so that average consumers would have access to well-conceived products. The latter believed a link existed between aesthetic value and purpose–that application and artistry should be fused. What united these two groups of disparate reformers was the identification of design as a vital means of domestic recovery, cultural reform, and even moral regeneration.

For two decades, this movement gained an important stronghold on design. However, the political and economic reality of war-torn Europe forever altered the landscape of the twentieth century, and art was no exception. By the 1920s, the Austrian Wiener Werkstätte (WW) began to decline. With economic downturns, the workshop turned to ceramics as a replacement for more costly production. At the same time, new leadership favored ornamentation with theatrical overtones. Not surprisingly, as craftwork was considered to be a suitable occupation for “ladies,” the ceramic department at WW was largely made up of women who submitted to the management’s preference for highly decorated items. In 1925, at l’Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes held in Paris, the ceramics presented by the WW were highly criticized for backsliding into baroque style. The ceramic department was chastised for work that was “too pretty,” and a “feminine aesthetic” became the scapegoat for the eventual failure of the Wiener Werkstätte.

The time also proved very difficult for the Bauhaus school. By 1925, the political and philosophical landscape became too hostile, and the Bauhaus moved from Weimar to a more hospitable location in Dessau. Soon after the move, however, a number of contributing factors caused the ceramics division to close, including the poor economic state of Germany, the death of master potter Max Krehan, and the departure of master sculptor Gerhard Marcks, who left to become head of the School of Fine and Applied Arts in Halle-Saale, Germany.

Susi Singer

Born in Austria in 1891, Susi Singer was a victim of the malnutrition that followed World War I, which left her permanently frail and crippled. However, at the age of seventeen, Singer received a scholarship to train at Wiener Werkstätte. It was here that she learned to create her exquisite ceramic figures. After sixteen years at the Wiener Werkstätte, she married a coal miner and moved to Grünbach. She soon established her own studio, but she also continued to supply the Wiener Werkstätte with her celebrated ceramic creations. Because she was married to an Aryan, she was not threatened by the anti-Semitic fervor present in Austria at that time; however, when her husband died in a tragic mining accident, things changed. Left with a son, Peter, just two months old, 47-year-old Singer moved back to Vienna to stay with her sister and mother. Life there became difficult because of the rise of the Third Reich. Streets were full of Nazi flags, and Singer, sensing the danger, applied for permission to go to the United States, obtained her visa, and fled.

In America, her repertoire of images increased to include life situations reflective of Hollywood, the California lifestyle, and the modern woman. For Singer, a woman of diminutive stature, it was perhaps a way to play out her dreams and fantasies. Whether depicting mythological or biblical figures, torch song singers, romantic heroines, or humorous vignettes, her flowing, elongated forms exist in obvious contradiction to her life in war-torn Europe and her own malformed body. Taking into account the context of the time—the “roaring twenties”—, a more realistic evaluation of Singer’s work and that of some of her more successful associates will justify the work’s lighthearted side. As a plastic medium well suited to manipulation, clay, with its bright array of colorful glazes, was the perfect material for sculpting the wide-ranging cast of fanciful or nostalgic characters that Singer created for her patrons. Singer’s style was refreshing. In a 1948 review of her work by Arthur H. Miller, a Los Angeles Times art critic, called her pieces “miracles of imagination, observation, grace, humor, freedom and amazing craftsmanship.”

Marguerite Wildenhain

Almost at the same time Singer became involved in Wiener Werkstätte, Wildenhain became a student at the Bauhaus, where, after mastering the fundamentals of ceramics, she went on to design superbly formed, functional tableware for industrial production. When the Bauhaus moved to Dessau, and Marcks took the job at Halle-Saale, he recommended Wildenhain as the head of the Ceramics Department. There, in addition to her teaching responsibilities, Wildenhain designed wares for the famous Royal Berlin porcelain factory. The tranquility she found in Dessau, however, was short-lived. Seven years later, the Nazis purged German schools of non-Aryan teachers, forcing Wildenhain to relocate to Holland. Here, she established a studio and won awards at the 1937 international exhibition in Paris, “Art et Technique,” for her studio “pots” and for objects designed for production. However, like Singer, Wildenhain could not outrun the spread of the Nazi movement in Europe, and she was also forced to flee to the United States.

Ultimately, Wildenhain settled in the hills above Guerneville in Northern California, where she and others attempted to establish a community of European craftsmen-teachers, similar to the Bauhaus. After eight years of developing the site and recruiting artist-teachers, the new school, called Pond Farm, was opened. Unfortunately, the community failed four years later. Wildenhain stayed on, determined to make Pond Farm her permanent home and pottery studio. She fought heroically to establish herself in the remote area, where hardship went hand in hand with accomplishment. She succeeded in establishing a well-known and respected summer school where she trained many future potters and sculptors with a strict vision of what it meant to be a craftsman, insisting that an artist’s life must involve total commitment and could not be separate from day-to-day life.

In the years that followed her 1952 appearance at Scripps College as a guest artist, Wildenhain made numerous workshop appearances throughout the US, visiting all but two states. These workshops allowed her to demonstrate her remarkable skill at the potter’s wheel and voice her philosophy of art and life as one. Wildenhain advocated basic training in the technical aspects of ceramics, along with drawing and sculpting assignments and exercises to increase the artist’s understanding of texture, space, and volume. In her 1973 book The Invisible Core, she wrote that an artist needs to observe the patterns of nature and to know art history; an artist must be well read and have a mastery of language. Above all, though, an artist should have strength of character, perseverance, dedication, and honesty.

By the 1970s, Wildenhain’s celebrity had started to wane in the United States. In the face of the “ceramic revolution” initiated through Peter Voulkos’ abstract-expressionist approach to clay at Otis Art Institute, Wildenhain’s traditional underpinnings fell out of favor with some. Referring to this type of experimentation in The Invisible Core, she wrote, “pottery, cut open, rolled up, smashed and deformed . . . hailed by our jurors as masterpieces of ingenuity and talent . . . though new, this will not save them from being ‘old stuff’ tomorrow.” Originally in awe of her proficiency, Voulkos and his followers later became critical of Wildenhain, labeling her methods as too restrictive.

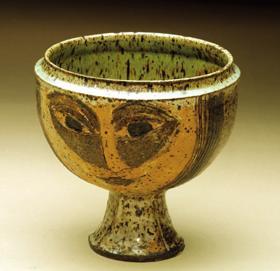

Wildenhain’s earlier aspiration to become a sculptor must be noted; her work followed an evolution that moved her closer and closer to this objective. Changes were subtle at first: images of nature drawn on her vessels soon graduated to vignettes of the people and animals she saw during her travels or within her community. At a more advanced stage, she created tiles that acted as the canvases for these drawings. Later still, she pierced these tiles or molded open relief work to add dimension. Eventually, freestanding figures became a vigorous part of her repertoire, finally fulfilling her original dream of becoming a sculptor.

Conclusion

Just as Susi Singer’s delicate, colorfully-glazed creations reveal her frail yet hopeful nature, so too do Wildenhain’s earth-colored, often raw, sturdily-constructed compositions expose her rustic, solitary life. It is our sincere desire to present the fascinating study of the similarities and contrasts between these two remarkable women who—despite the limitations of their sex and the world around them, their dislocation from their culture and the disappointment wrought from the failed social experiments of twentieth century Europe—did not give up on their artistic pursuits. They persevered, and Women’s “Werk” is the celebration of their achievements.